Two factor authentication (2FA) is an amazing invention. For one thing, it can significantly increase the security of your online accounts without significantly increasing the hassle of logging in. Additionally, the most popular 2FA algorithms are available in both free software and proprietary software implementations. This weekend, I reverse engineered Symantec's proprietary 2FA token solution with the goal of creating a free software alternative.

Motivation

Why did I do this? Well, like many people in the world, I use PayPal to send and receive money. To protect the security of my account, I use 2FA. Normally, when you use 2FA, the service provider presents a barcode to you that you can scan with any one of a number of applications (Authy, Duo Mobile, FreeOTP, Google Authenticator, etc.). However, PayPal uses the Symantec Validation and ID Protection Service (formerly Verisign Identity Protection) for their second factor. PayPal probably didn't want the overhead of managing a database of user tokens, so they went with Symantec's managed solution. My problem with this is that, while I can use Authy for all of my other accounts, I need to use the VIP Access app for PayPal only. So, I guess my reasoning here was:

- Having multiple apps that do essentially the same thing seemed inefficient

- The VIP Access app for iOS is pretty ugly (in my opinion)

- I would prefer to have all of my tokens generated with one application/hardware device

Since it appeared as though no one else had done so, I decided to reverse engineer Symantec's VIP client myself.

Prior Work

I originally started working on this project around this time last year. I worked on it on and off for a few months, but I never made much progress. This was partially due to the fact I was attempting to de-obfuscate a heavily obfuscated Android application. I eventually got tired of that project and set it aside for a rainy day.

That "rainy day" came earlier this year when I saw this post, in which someone reversed their bank's obfuscated Android 2FA application in order to create a hardware token for it. Interestingly enough, the obfuscation used in that application was strikingly similar to the kind I found the VIP Access Android app using. Despite this newfound knowledge, I was still unable to deobfuscate many of the important portions of the application. At this point, I still thought that VIP Access used a proprietary algorithm to generate one time passwords.

Earlier this month, I found this script, in which I learned that VIP Access didn't use a proprietary algorithm to generate the tokens. I also learned that Symantec had released VIP Access applications for OS X and Windows. While this token extractor would have almost fit my needs, I really didn't want to have to rely on Symantec's proprietary client in order to generate these token keys. Plus, this script only works on OS X, so Linux and Windows users would be unable to extract their keys. So, eager to try out my recently-purchased disassembler (Hopper), I downloaded the VIP Access application and got to work.

The Process

Analysis of the Client-Server Communications

I started by opening the VIP Access application. The first window that appears indicates that the program is "Activating VIP Access". This would make sense if the program was calling out to some server to activate, so I fired up mitmproxy to watch the communications.

Here's an example of a provisioning request made by the application that would

be POSTed to https://services.vip.symantec.com/prov:

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8" ?><GetSharedSecret Id="1412030064" Version="2.0" xmlns="http://www.verisign.com/2006/08/vipservice" xmlns:xsi="http://www.w3.org/2001/XMLSchema-instance"><TokenModel>VSST</TokenModel><ActivationCode></ActivationCode><OtpAlgorithm type="HMAC-SHA1-TRUNC-6DIGITS"/><SharedSecretDeliveryMethod>HTTPS</SharedSecretDeliveryMethod><DeviceId><Manufacturer>Apple Inc.

</Manufacturer><SerialNo>7QJR44Y54LK3

</SerialNo><Model>MacBookPro10,1

</Model></DeviceId><Extension extVersion="auth" xsi:type="vip:ProvisionInfoType" xmlns:vip="http://www.verisign.com/2006/08/vipservice"><AppHandle>iMac010200</AppHandle><ClientIDType>BOARDID</ClientIDType><ClientID>Mac-3E36319D3EA483BD

</ClientID><DistChannel>Symantec</DistChannel><ClientInfo><os>MacBookPro10,1

</os><platform>iMac</platform></ClientInfo><ClientTimestamp>1412030064</ClientTimestamp><Data>mxk5NtUnCwd36GEpQq6+Zmnh+rPKDePuS/XYci6/WD0=</Data></Extension></GetSharedSecret>

Because that request is really hard to read, I've run it through an XML beautifier:

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8"?>

<GetSharedSecret Id="1412030064" Version="2.0" xmlns="http://www.verisign.com/2006/08/vipservice" xmlns:xsi="http://www.w3.org/2001/XMLSchema-instance">

<TokenModel>VSST</TokenModel>

<ActivationCode></ActivationCode>

<OtpAlgorithm type="HMAC-SHA1-TRUNC-6DIGITS" />

<SharedSecretDeliveryMethod>HTTPS</SharedSecretDeliveryMethod>

<DeviceId>

<Manufacturer>Apple Inc.

</Manufacturer>

<SerialNo>7QJR44Y54LK3

</SerialNo>

<Model>MacBookPro10,1

</Model>

</DeviceId>

<Extension extVersion="auth" xsi:type="vip:ProvisionInfoType" xmlns:vip="http://www.verisign.com/2006/08/vipservice">

<AppHandle>iMac010200</AppHandle>

<ClientIDType>BOARDID</ClientIDType>

<ClientID>Mac-3E36319D3EA483BD

</ClientID>

<DistChannel>Symantec</DistChannel>

<ClientInfo>

<os>MacBookPro10,1

</os>

<platform>iMac</platform>

</ClientInfo>

<ClientTimestamp>1412030064</ClientTimestamp>

<Data>mxk5NtUnCwd36GEpQq6+Zmnh+rPKDePuS/XYci6/WD0=</Data>

</Extension>

</GetSharedSecret>

Notice how the values for Manufacturer, SerialNo, Model, ClientID, and

os all have newline characters in the strings? This will be important later.

For now, let's look at the response we get back.

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8"?>

<GetSharedSecretResponse RequestId="1412030064" Version="2.0" xmlns="http://www.verisign.com/2006/08/vipservice">

<Status>

<ReasonCode>0000</ReasonCode>

<StatusMessage>Success</StatusMessage>

</Status>

<SharedSecretDeliveryMethod>HTTPS</SharedSecretDeliveryMethod>

<SecretContainer Version="1.0">

<EncryptionMethod>

<PBESalt>u5lgf1Ek8WA0iiIwVkjy26j6pfk=</PBESalt>

<PBEIterationCount>50</PBEIterationCount>

<IV>Fsg1KafmAX80gUEDADijHw==</IV>

</EncryptionMethod>

<Device>

<Secret type="HOTP" Id="VSST26070843">

<Issuer>OU = ID Protection Center, O = VeriSign, Inc.</Issuer>

<Usage otp="true">

<AI type="HMAC-SHA1-TRUNC-6DIGITS"/>

<TimeStep>30</TimeStep>

<Time>0</Time>

<ClockDrift>4</ClockDrift>

</Usage>

<FriendlyName>OU = ID Protection Center, O = VeriSign, Inc.</FriendlyName>

<Data>

<Cipher>ILBweOCEOoMBLJARzoeUIlu0+5m6b3khZljd5dozARk=</Cipher>

<Digest algorithm="HMAC-SHA1">MoaidW7XDzeTZJqhfRQCZEieARM=</Digest>

</Data>

<Expiry>2017-09-25T23:36:22.056Z</Expiry>

</Secret>

</Device>

</SecretContainer>

<UTCTimestamp>1412030065</UTCTimestamp>

</GetSharedSecretResponse>

As you can see, these requests use XML and most of the fields are pretty self explanatory

To start reversing this protocol, I used HTTP Client1 to send

modified POST requests and note the responses. Interestingly enough, I could

change most of the values and still get "valid" responses. I put "valid" in

quotes because, as I would later learn, the value of Data would determine

whether the credential would be activated or not. I didn't get very far by

poking the provisioning server, so I moved on to a static analysis of the

program.

Searching the Binary for Clues

Static Analysis

To start, I decided to look for some functions involved in parsing the

response from the server. The decryptCipher method in

ProvisioningController looked promising, so I took a look at the

disassembled code. Lo and behold, one of the lines read:

eax = CCCrypt(0x1, 0x0, 0x0, STK29, 0x10, eax, edi, STK25, ecx, esi, edx);

From the CCCryptor man page:

CCCrypt(CCOperation op, CCAlgorithm alg, CCOptions options,

const void *key, size_t keyLength, const void *iv,

const void *dataIn, size_t dataInLength, void *dataOut,

size_t dataOutAvailable, size_t *dataOutMoved);

From this, I could tell2 that CCCrypt is performing a decrypt

(op = 1 = kCCDecrypt) operation using AES-128

(alg = 0 = kCCAlgorithmAES128) with no padding and no ECB (options = 0)

and a 16-byte keylength (keyLength = 0x10, to be expected with AES-128-CBC).

I didn't try to find out the key and IV just yet, so I moved on to the next

interesting method in ProvisioningController, prepareHmacInRequest:

...

CCHmac(0x2, esi, edi, STK29, eax, &var_44)

...

And from the CCHmac man page:

CCHmac(CCHmacAlgorithm algorithm, const void *key, size_t keyLength,

const void *data, size_t dataLength, void *macOut);

This told me that the HMAC algorithm being used was SHA-256

(algorithm = 2 = kCCHmacAlgSHA256).

Unfortunately, static analysis could only go so far and while I did investigate other objects and their methods, most of them were dead ends. From there, I moved on to the dynamic analysis.

Dynamic Analysis

Debugging a program in Hopper is incredibly easy since you can set all the breakpoints in the GUI and read out the memory at arbitrary addresses with simple commands.3 Thankfully, VIP Access doesn't have any debugging protections, nor does it have any memory obfuscation, so finding the inputs to each of the important functions was trivial.

I started with CCCrypt, the function that decrypts the OTP token secret in

the provisioning response. I set breakpoints where I saw the pointers to the

key, iv, and dataIn variables were being set. From there, I followed

those pointers to the areas in memory where those values were stored and

dumped them.

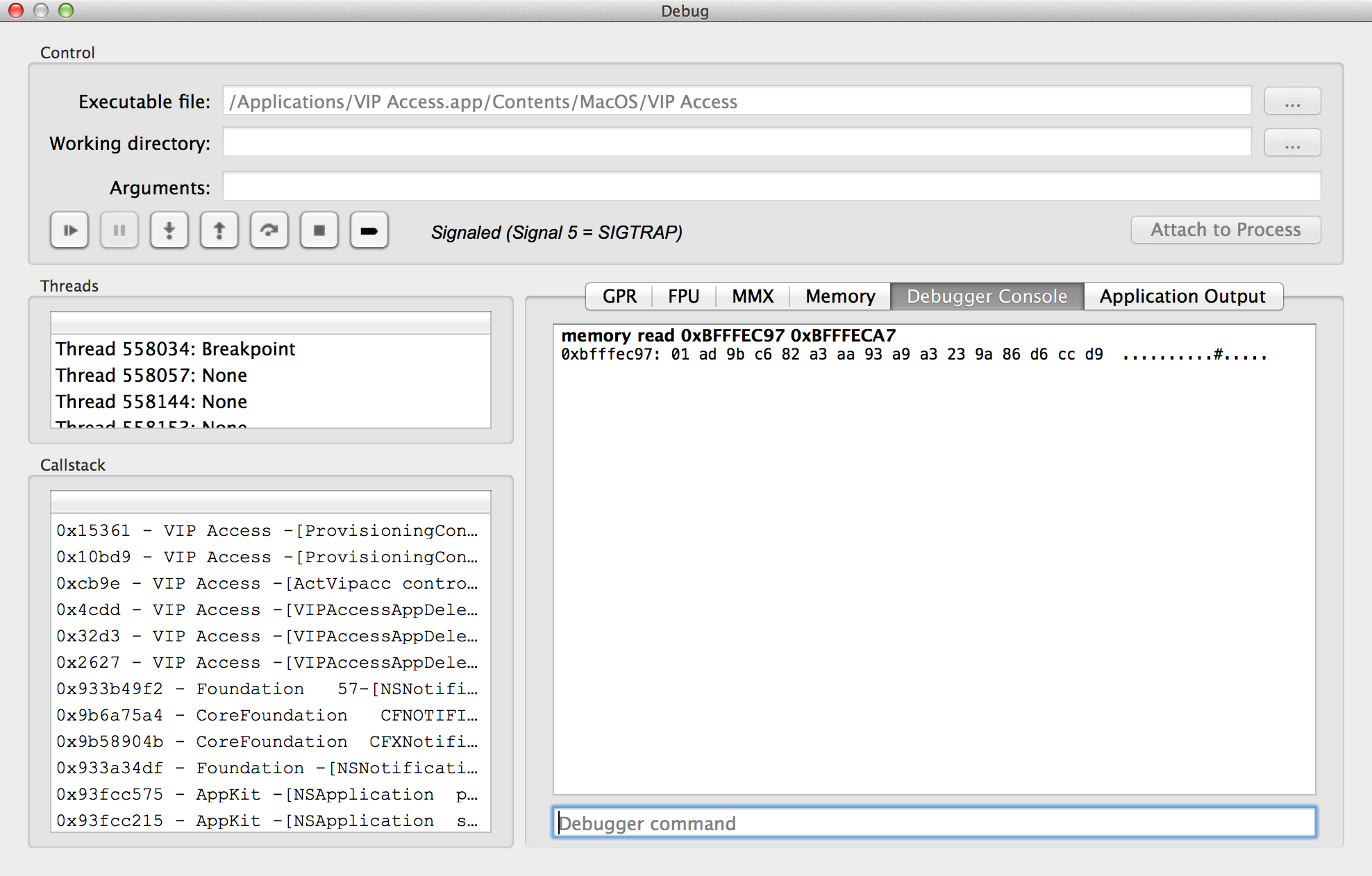

First I dumped the key:

After dumping it, I decided to try it a few more times to make sure it

wouldn't change—thankfully, it didn't, so I knew it was a static key.

But if the key didn't change, what did? None other than the IV, of course! I

set up a mitmproxy capture while performing my dynamic analysis to confirm

that, yes, the IV used to decrypt dataIn was the same as the one in the

provisioning response (base64-decoded). Similarly, dataIn ended up being the

base64-decoded value of Cipher. From there, I wrote a small Python function

to do the decryption myself. After removing the padding, I ran

oathtool --totp with the hex-encoded OTP token secret to confirm that it was

actually the correct secret. And it was! This was my first major victory, but

there was a setback—when I tried playing back a valid captured request,

I would get a proper response, but when I went to check the token

online, Symantec said the credential ID was invalid. Even after updating

the time in the request, the ID was still reported as invalid, so I knew that

the value of Data in the request was significant in some way.

Looking back on the static analysis, the method I hadn't dynamically analyzed

yet was prepareHmacInRequest in ProvisioningController. Again, by

strategically setting breakpoints, I was able to determine both the HMAC key

and the data used to generate it.

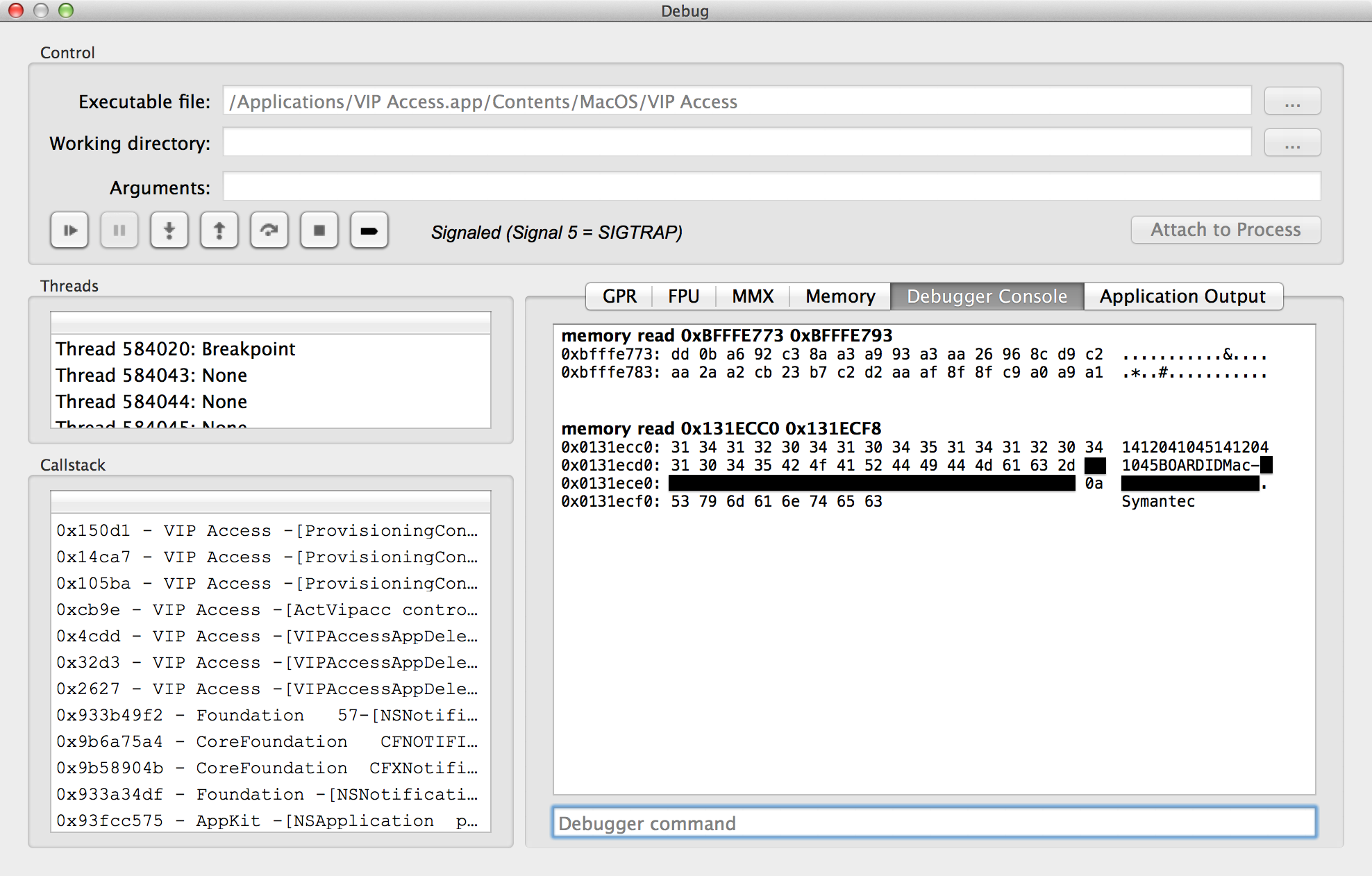

The 32-byte dump is the static HMAC key and the 56-byte dump is the data that

is HMAC'd (the blacked out portion is the unique part of my board ID). Oh, and

remember earlier when I noted that ClientID had a newline character in it?

Well, you can see it in the data to be HMAC'd (0x0a), right at the end of the

blacked out bytes. Apparently, when the program uses ioreg to retrieve the

computer information (-[ProvisioningController getDeviceInfo:]), it doesn't

strip the newline characters (which a simple tr -d '\n' would have fixed,

but I digress). It doesn't matter, of course, since the VIP provisioning

system will accept any values for those keys.

Writing a Free Client

With both the HMAC key and the token encryption key, I was able to write a Python program to automatically provision a VIP Access credential and generate both an otpauth URI and a QR code of that URI. You can find the code I wrote in its repository on GitHub.

All in all, it was pretty straightforward to write a client for this service

since, at it's core, it's a simple HTTP POST with some hashing and decryption.

The only obstacle I encountered was that the lxml.ElementMaker API wasn't

properly generating the namespace attributes of the Extension tree, but I

got around that by creating a "template" to plug the dictionary of values into.

While it isn't the "correct" way to generate XML with Python, in this instance

it was the only way. Oh, and I haven't yet figured out how the response digest

HMAC is generated, but the program works without it.

In the future, I might add the capability to emulate the mobile version of VIP Access and I'll definitely add more error-checking to the code. Right now, all it does it check whether the OTP token actually functions by sending a separate request to Symantec to confirm that it does work. I might even turn it into a full Python module, complete with class definitions and all that fancy stuff.

Extras

There was some code in there that had to do with updating a token's details

from the server (-[ProvisioningController updateNonACRequest:]), but I

didn't really pay attention to it. I assume it's there to handle updating the

token when it expires, but because the strings were xor-obfuscated and since

reversing it wasn't necessary for my purposes, I left it alone. Why was that

portion of the code obfuscated? Only the developers know. Speaking of which...

If you're curious, you can learn the names and usernames of some of the

developers of this application by looking at the strings in the VIP Access

binary and the .svn directory in the root of the VIP Access.app folder.

Conclusion

Hopefully, the work I've done will benefit the Internet community by facilitating the interoperability of computer programs and, more specifically, by allowing anyone on any operating system to use Symantec's VIP service.

Aside from the ugly iOS app, this experience has actually given me a lot of respect for the VIP service. It seems to to be a very robust system, capable of using any implemented OTP algorithm by simply changing some of the attributes in the protocol. Its inclusion of expiration dates for the tokens is also a good idea, and I'm sure token revocation is implemented on the backend. In other words, the people who built this system really knew what they were doing.

Lessons learned:

-

If you want to mess with an amateur software reverse engineer, add as many roadblocks as possible. i.e., obfuscate your code, obfuscate objects in memory, etc. This, of course, will not deter a professional in the field.

-

Don't leave testing code in the production version of any application you write. Doing so can potentially leak sensitive information (developer names could be used by someone to socially-engineer their way into a company, Kevin Mitnick style).

-

When you package an application, be absolutely sure to remove any hidden version control directories. If you don't, you can potentially leak sensitive information (developer usernames, among other things).

-

While

curlwould have worked just as well in this instance, a GUI can be faster for experimentation. ↩ -

When you want to know what constants are used in a function's arguments, try looking in the header files. ↩

-

Yes, I know

gdbcan do the same things, but having a GUI makes noticing patterns so much easier. Plus, I already spent the $89 for the program, so I might as well use it! ↩